Review: Coming Out Republican, A History of the Gay Right

Suzanna Krivulskaya reviews Neil J. Young's new book from the University of Chicago Press

"Gay Republican… How do you exist?"

Comedian Moshe Kasher opened his 2017 interview with Ben Coleman by feigning incredulity. At the time, Coleman was the vice president of the Los Angeles chapter of Log Cabin Republicans, the nation's oldest gay Republican organization, whose 10,000 members' very existence perplexed liberal observers like Kasher.

Coleman explained that being gay was only one part of him. The organization he represented, he said, labored tirelessly to change the Republican Party's stance on gay "issues." The interviewer remained unpersuaded. "Is homophobia okay," Kasher asked, "if it serves the free market?"

Neil J. Young's new book Coming Out Republican: A History of the Gay Right explains why queer conservatives are not anomalous. In 2020, 15% of LGBT voters were registered Republicans. Over the past thirty years, GOP candidates have enjoyed even broader support among gay and lesbian voters. Formal political organizations like the Log Cabin Republicans have been around for half a century, and one of the founders of the homophile movement was a staunch conservative.[i]

This genealogy alone ought to make gay Republicans seem less foreign to skeptics who demand that queerness be homogenous. Young's book convincingly establishes that the seemingly incongruous identity has shaped U.S. politics for the better part of the last century. Through a compelling composite portrait, Young makes gay Republicans legible as active architects of both a particular kind of queerness and a version of political conservativism.

Young's historical analysis moves beyond the merely descriptive. No reader will walk away confused about where Young stands in the final assessment of the compatibility between queer lives and modern Republican values. Still, Young manages to tell a story whose subjects would recognize themselves in the narrative, even as the author's assessment of their contributions is broadly critical. Gay Republicans, Young explains, have been ultimately responsible for challenging some of their party's "worst inclinations" while simultaneously "helping advance some of its extremism" (12).

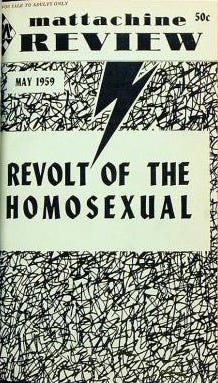

The story begins at the center of early homophile organizing. Dorr Legg, a libertarian Republican who happened to be gay, was hosting the October 1952 meeting of the Mattachine Society in his Los Angeles apartment when several members decided to create a new organization devoted to producing positive portrayals of homosexuality. ONE Magazine, the first homophile periodical in the nation, was established shortly thereafter. Legg would quit his well-paying job and focus on the publication full-time.

During his tenure, Legg’s libertarianism emboldened him to push for more than just improved public opinion. In 1961, Legg advocated for creating a "Homosexual Bill of Rights" that would not only defend homosexuality but also demand civil equality. Ironically, the idea frightened Legg’s more left-leaning queer activists, who worried that public opinion would suffer were homosexuals to ask for too much too fast. Legg was outraged—but outnumbered. In another decade, the mainstream gay rights movement would align with the New Left and finally demand fair treatment and civil equality. Gay Republicans, on their end, would step back into the closet.

Closeted architects of modern Republicanism, such as Marvin Liebman and Robert Bauman, entered politics in the 1960s and 1970s to promote a conservative agenda while hiding their queerness. The men were founding members of Young Americans for Freedom and of the American Conservative Union. Bauman was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1973 and became one of the most well-founded Republican politicians by the end of the decade. Notably, Liebman and Bauman did not view their sexuality and their politics as incompatible. The Republican commitment to small government would take care of the seeming incongruity: the state had no business meddling in the private sexual lives of citizens.

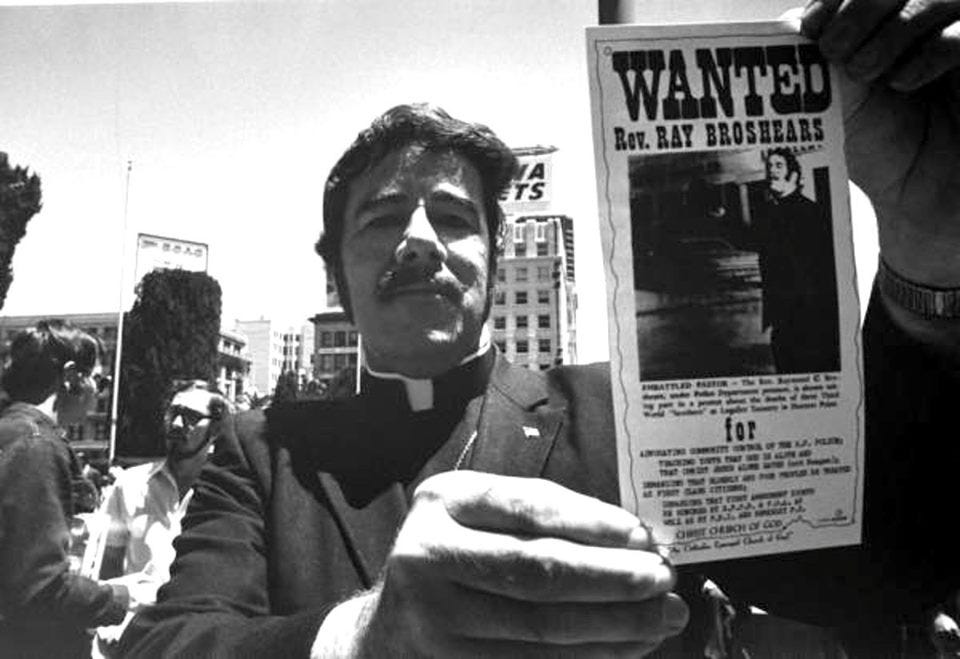

Outside of Washington, some gay Republicans argued that progress required visibility. In San Francisco, the radical Reverend Raymond Broshears took his belief in limited government and individual freedoms to mean the right to respond to anti-queer policing with violence. His short-lived organization, the Lavender Panthers (1973-1974), armed gay and trans people to respond to harassment by law enforcement. The denizens of Harvey Milk’s San Francisco did not celebrate Broshears in the same way that many of Oakland’s African American residents praised the Black Panthers.

Elsewhere in the country, gay conservatives began to form organizations that would use the politics of respectability to gain the public’s sympathy and to persuade their party that queerness was compatible with fiscal conservatism, family values, and even religious traditionalism. The latter became challenging to argue following several high-profile 1980s sex scandals, which revealed that some of the GOP’s brightest stars turned out to be closeted homosexuals whose secret lives diverged from their public stances on sexual morality. In October 1980, Robert Bauman was running for re-election to the House of Representatives, when the FBI arrested him for soliciting the services of a sixteen-year-old male sex worker. Despite a brief publicity campaign designed to persuade the public that his "homosexual problem" could be solved with the support of his wife and community, Bauman lost his seat to a Democrat. The following year, Bauman's Congressional colleague from Mississippi, Jon Hinson, was arrested for performing oral sex on a Library of Congress clerk in a House of Representatives restroom. Hinson resigned and, unlike Bauman, eventually came out and became a gay rights activist. To conservatives' dismay, Hinson’s Congressional seat also went to a Democrat in a special election.

The AIDS epidemic ushered in new crises. In meeting untimely deaths, several closeted Republicans, such as the head of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, Terry Dolan, were revealed to have been gay all along. Their unsympathetic compatriots demanded that the already beleaguered homosexuals face state-sanctioned retribution. William F. Buckley infamously advocated that gay men infected with AIDS be forcibly tattooed on their buttocks to prevent the spread of HIV. Simultaneously, an emboldened conservative Christian coalition moved the GOP farther to the right on social issues.

Gay Republicans emerged from the crisis with a commitment to earn their civil liberties by engaging in respectability politics that would be palatable to their socially conservative colleagues. They would dress in suits, mingle with politicians who were generally hostile to queerness, and make a conservative case for marriage equality. With many civil liberties achieved during the Obama presidency, today’s gay Republicans have embraced the Make America Great Again agenda along with its strange anti-trans obsession that is almost certainly at odds with the Republican commitment to individual freedom.

Then again, the movement's demographics may explain the things it derides. While the group has seen some measure of ideological diversity (though it broadly agrees on fiscal conservatism, national security, and individual rights), most gay Republicans are white middle- and upper-class men. Their sexuality, they insist, is a private matter. They view themselves as conservatives who just happen to be gay—a stance that must feel natural to people unfamiliar with structural oppression. The lack of diversity in Young’s archive reinforces a broader point about which gay men feel at home in the Republican Party.

Coming Out Republican could also say more about religion. Young accounts for many of his protagonists’ Republican childhoods while treating their religious formation as almost incidental. The chapter on Rev. Ray Broshears, for one, demands more engagement with how precisely his faith, his ties to Billy James Hargis, and his subsequent renegade brand of Christianity influenced his activism and politics. Gay Republicans like Rich Tafel, who is mentioned in Young’s story and today self-describes as a "pastor, social venture strategist and facilitator of political dialogue," provide a fascinating glimpse into how religion and capitalism have intermingled in this movement all along.

Still, the book is a well-written and timely overview of a small but important fraction of LGBTQ+ people. Young's archival research and compelling storytelling make Coming Out Republican a vital resource for students of religion and politics. Recognizing gay Republicans’ full humanity—and not discounting them as self-loathing anomalies—is crucial for understanding the modern sexual regime. It also invites us to reassess whether there has ever been such a thing as "the LGBTQ+ community."

Suzanna Krivulskaya is Assistant Professor of History at California State University San Marcos. She specializes in modern U.S. history and studies the relationship between sexuality and religion. Her first book, Disgraced: How Sex Scandals Transformed American Protestantism (forthcoming from Oxford University Press), is a sweeping religious and cultural history of ministerial sex scandals in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

[i] The homophile movement was the name that activists used during this time period.